During my third year in college, I started to focus more on my studies. I threw myself into my books and into my homework, often staying late at the library until midnight and rolling into bed at 1AM. But my newfound work ethic was more mechanistic than passionate---I studied hard to achieve good grades and praise, not to develop my mind or even to gain a deeper understanding of history. My classes definitely made me work, but didn't necessarily make me think.

After my junior year, I decided to stay in Provo for half the summer. My history classes were usually demanding so I decided to take one history course in spring semester, thus focusing on one class for ten weeks. When I scrolled through the spring semester course offerings, one class stood up in particular: History 340, 20th Century Chinese History. I was intrigued. I had never taken any Chinese history classes, much less any contemporary history classes.

For my first two years at BYU, I had prided myself as an ancient historian---learning about the bas reliefs of Assyria and the aqueducts of Rome. But I had no tangible ties to Assyria or Rome, only a vague interest towards antiquity. Contemporary Chinese history, on the other hand, offered me an in-depth view into my heritage and ancestry. My grandparents fled China in the late 1940s to escape the Communists. When I was little, my grandmother filled my head with stories about the dreaded CCP. It was an easy decision to make---I signed up for History 340.

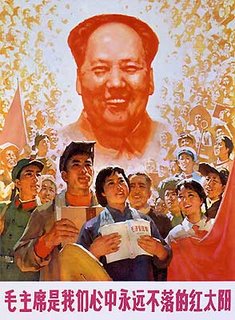

On the first day of class, Dr. Michael Murdock used a slideshow to introduce the class to modern China. He showed us pictures of the green countryside juxtaposed against the gray-skies of Beijing. He showed us a land full of contradictions---tradition and modernism, communism and capitalism, secrecy and over-exposure, isolation and community. I knew this history class was going to be different, and not only because of my cultural descent. Our first assignment was to send an email to Dr. Murdock and to tell him about why we took his class, why we studied history, our historical interests, and what we wanted to do with our lives. I didn't even know this professor, but he seemed to have a deep interest in me.

As the spring semester continued, I saw further proof that History 340 was unlike any other class I had ever taken. We regularly watched movies that tackled aspects of modern Chinese history, like "To Live," and "Red Sorghum." We read autobiographies by people who lived through the events we were studying, like The Private Life of Chairman Mao and Red China Blues. And in class, we were readily encouraged to ask questions and to engage in discussion.

Dr. Murdock's approach to teaching history was simple. He didn't want his students to leave his class with only the ability to regurgitate names and dates. He wanted to equip his students with the ability to think and to re-think history. Our term papers revolved around questions like, "How are nationalism and imperialism linked in the creation of modern China?" and "How do individual identity and communal identity clash in 20th century China?" He used the study of modern Chinese history as a vehicle to gain greater understanding of the world around us.

One of the requirements of the course was to meet with Dr. Murdock on a one-on-one basis to discuss our term paper. So after class one day, I knocked on the professor's door expecting a brisk meeting. Instead, Dr. Murdock talked to me for half-an-hour, asking me about my historical interests and inquiring about my Chinese ancestry. Throughout my tenure at BYU, Dr. Murdock always made time to talk with me, whether it was about history, about grad school, or about my struggles over my faith. His door was always open and he always greeted me with a smile.And so, when I found out last week that Professor Murdock didn't receive tenure, I felt very sad. Mostly, I felt sadness for future BYU students who won't have the pleasure of taking a class with Dr. Murdock. They will miss out on the chance to become real historians, rather than regurgitators of cold facts.

Professors who truly care about students are already few and far between. Professors who learn every name of their students are even rarer. It's disappointing to me that professors often have to choose between research interests and student interests. At a big teaching university like BYU, professors often have to teach three classes per semester as well as crank out articles and books. Many professors fail to form any close bonds with their students because they're too busy trying to publish. And I can't blame them. I can't blame someone for trying to keep their job.

But I wish professors like Dr. Murdock didn't have to suffer the cruel consequences of the "publish or perish" methodology. He took an honest interest in his students and I feel he's being punished for it. In the end, I think everyone loses---Dr. Murdock, the university, and especially, the students.